~ / Territorialization: Branding, Imperialism, and Consumption

September 24, 2024

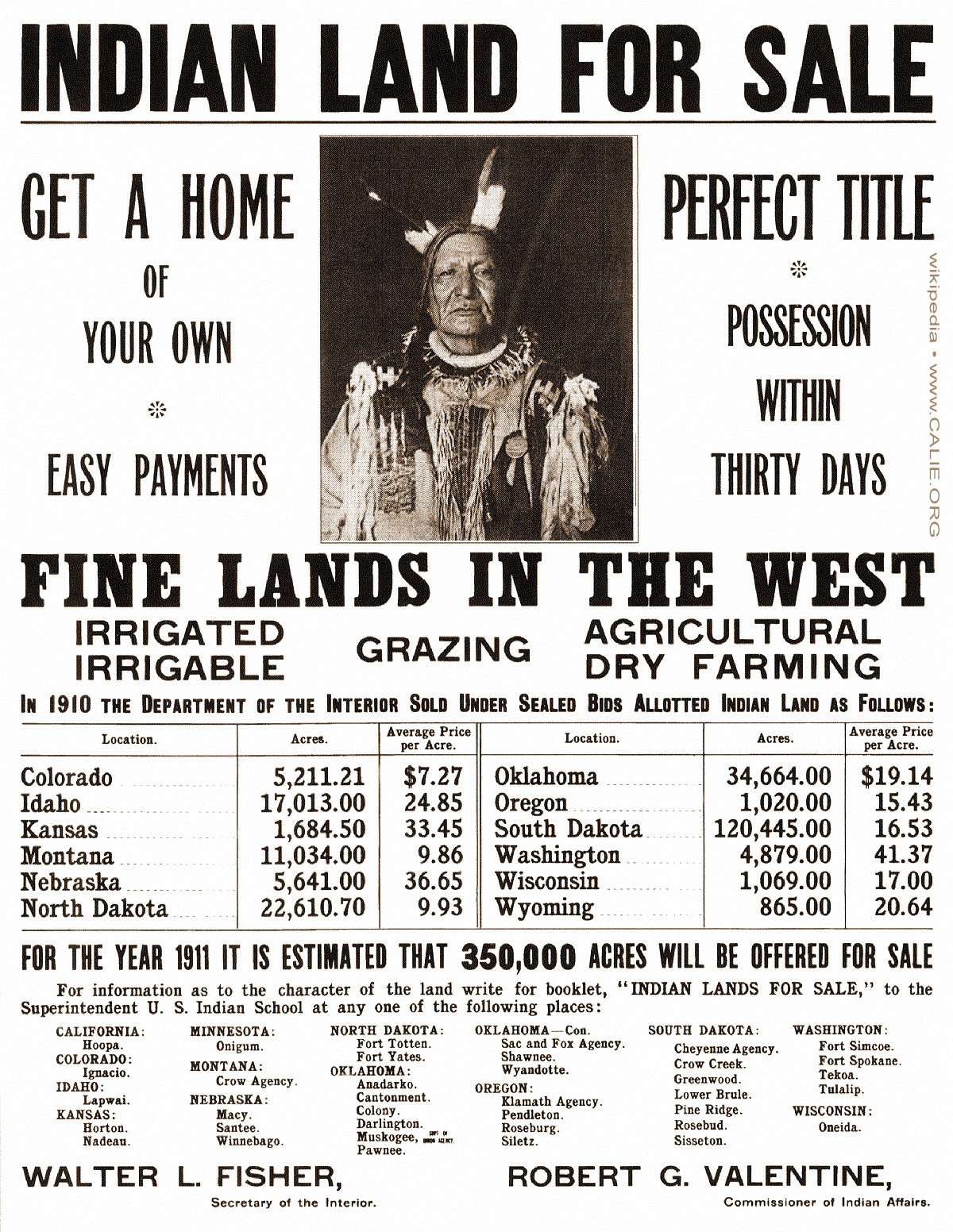

During the American westward expansion, the United States systematically displaced Native Americans and divided the land into parcels that were then sold to speculators and the emerging landed gentry. This parceling of land signifies the productive capability of a powerful force to create territories by erasing what existed before. It mirrors the contemporary practice of branding, where companies carve out niches in both the marketplace and the collective consciousness. This process, which I call territorialization, deliberately defines spaces but strips them of their previous history and significance. The early stages of Australian colonization followed a similar path, where industrialists found opportunities in newly territorialized spaces to exploit laxer labor, taxation and environmental regimes.

Territorialization is a natural outcome of capitalism, paralleling how monopolies form. Just as businesses monopolize entire industries, brands monopolize cultural meaning. When a company like Nike or Google positions itself as the leader in its field, it doesn’t just sell products; it shapes public perception. Alternatives become marginalized, similar to how colonial powers displaced indigenous cultures. Gramsci’s concept of cultural hegemony explains how dominant ideologies infiltrate daily life, becoming accepted as "common sense." Branding, in this way, embeds itself in culture, defining norms and displacing alternative expressions. The modus operandi of branding is to become "common sense" to join in and sublinate into the hegemonic culture.

Atomization and individualization are the symptoms of large-scale territorialization happening within our mental and social spaces. In today’s consumer society, people are encouraged to own personal tools, products, and identities, creating micro-territories of consumption. This individual ownership, though seemingly empowering, often reinforces the dominance of brands. Even collective alternatives, such as laundromats or co-working spaces, eventually become commodified and absorbed into branded ecosystems. The result is a near-inescapable cycle where every aspect of life is territorialized by corporate entities.

In the technological world, this dynamic is particularly pronounced. Users become comfortable residing within the walled gardens of companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Adobe, where territorialization is nearly absolute. These ecosystems are designed to make it difficult for users to leave, much like monopolies in physical markets. The complexity of technology often discourages people from creating their own digital spaces, even though modern AI has made it increasingly possible to cultivate personal "gardens" outside of these branded territories.

This overarching process of territorialization is not limited to technology or consumer products. It reflects the broader imperialistic logic of capitalism, which seeks to extend control over every possible space—physical, cultural, and ideological. Brands today function like the colonial powers of the past, conquering not lands, but minds and identities, with the ultimate goal of monopolizing meaning and desire in every facet of life.

In conclusion, the practice of territorialization, both in historical imperialism and modern branding, reflects the tendency of powerful forces to create and dominate spaces while erasing what came before. Branding has become a primary tool for this process in the post-colonial era, establishing monopolies not just in markets but in collective consciousness. As individuals are atomized into smaller consumption units, and technological ecosystems become ever more entrenched, the cycle of territorialization continues to shape the cultural and economic landscape.